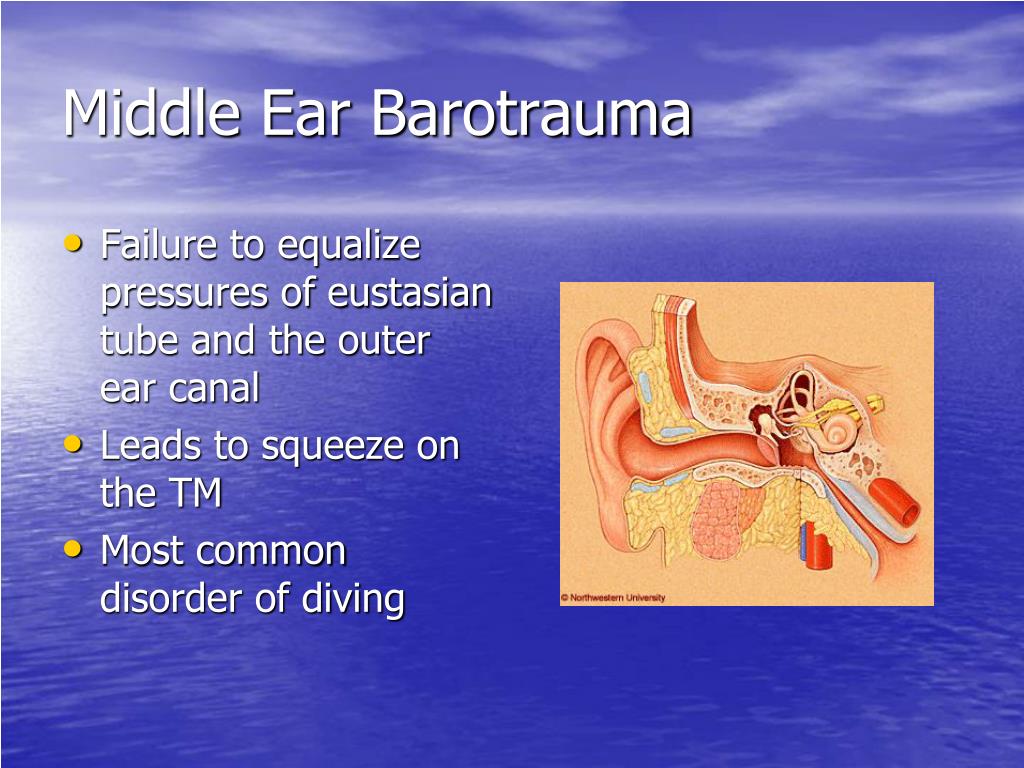

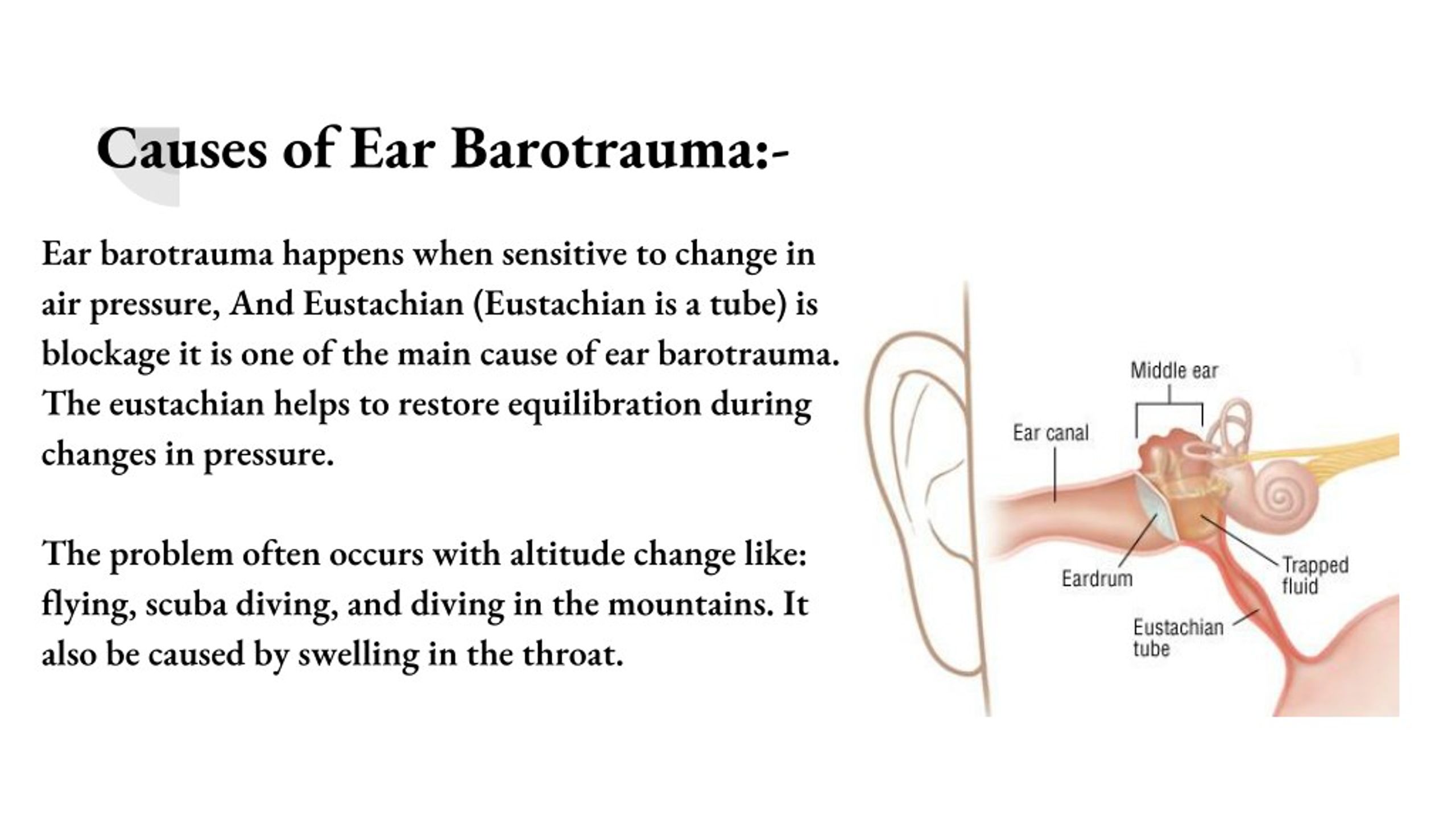

Middle-ear barotrauma in our patient caused pneumocephalus, as well as parenchymal and extra-axial hemorrhage.ĬT scanning was carried out because of severe, unrelenting headache in our patient, who had no neurologic abnormality. Intracranial complications of middle-ear barotrauma are rare. Because of rare but catastrophic cases like this, reverse valsalva and Eustachian tube catheterization are no longer in use. Autopsy showed an acute epidural hematoma overlaying the tegmen. Indeed, their study was prompted by the death of a 40-year-old patient within 2 hours after air insufflation via a Siegler speculum. Malby and Stewart ( 2) found tegmen tympani defects in 52% of 50 routine autopsy cases and showed that extension of air into the epidural space could occur with routine otolaryngology procedures by using a Siegles bulb or Politzer bag. Rupture through the tegmen tympani may potentially occur, especially if the bone is thin or deficient. If the Eustachian tube is not patent, there can be a “reverse squeeze” during ascent as pressure in the middle ear exceeds the ambient pressure. As the diver ascends, the same water pressure column decreases and release of gas from the middle ear through equalization of pressures is necessary, to compensate for the expanding volume of air ( 1). A 33-foot dive will double the ambient pressure from 1 to 2 atmospheres absolute. Following Boyle’s law, air within the middle ear will be compressed to a volume inversely proportional to the pressure exerted by the overlying water. A follow-up CT scan showed complete normalization 9 months after the initial event.īarotrauma to the middle or inner ear can occur during descent or ascent in scuba diving and reflects failure to equalize the pressure between the middle ear and the ambient pressure. An exploratory tympanotomy ruled out this possibility, and packing of the round window niche with fat was performed. A new CT showed resolving left epidural hematoma, and investigation for meningitis was negative.įour months after the scuba-diving accident, imbalance and subtle left tympanic membrane erythema raised the question of perilymph fistulization. Three weeks later, after skydiving, headache reappeared, accompanied by nausea and left facial numbness. The management of the intracranial findings was conservative. Both mastoids were extensively pneumatized. No bone disruption could be identified, but bone could not be clearly identified along the entire tegmen tympani of either temporal bone. 2) done 24 hours after the event showed minimal opacification of left mastoid air cells without air fluid levels. No abnormality was seen within the temporal bone, but a high-resolution temporal bone CT scan ( Fig. Continuing headache despite treatment with analgesics prompted a CT scan ( Fig 1), which showed parenchymal hemorrhage within the left temporal lobe overlying the petrous bone, as well as epidural blood and gas in the middle fossa.

Otologic and neurologic examinations did not reveal deficits. He was subsequently seen at the emergency room with persistence of otalgia, decreased hearing on the left, and vertigo. At the surface, his “left ear exploded.” His instructor told him to redescend to 30 feet to “recompress,” but this did not produce improvement. A 31-year-old man experienced severe left ear pain while ascending from a 30-foot scuba dive.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)